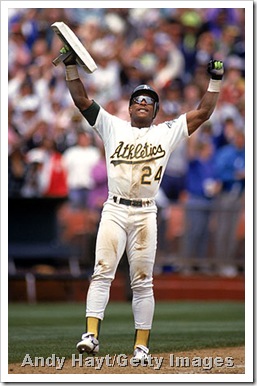

Now I’m not about to tell you brand new Hall of Famer Rickey Henderson wasn’t a great player. Of course he was. And I loved him growing up – who didn’t? He was a swashbuckling stolen base machine who referred to himself in the third person.

That said, if anyone is a better testament to selfishness, I’d like to meet him. Rickey made it an art form.

Now, before any fans of the 45 teams Rickey played for jump down my throat, I’ll point out that in terms of sheer talent, he’s up there with anyone. I feel like his talent might be overlooked just because he wasn’t a prodigious slugger in an era where that was beginning to come into vogue. (Though his 297 home runs are nothing to sneeze at) Rickey had an outstanding eye at the plate. And you can’t discount someone who had 130 steals in a season and 1,406 in his career.

Most impressively, as Joe Posnanski of SI correctly pointed out, Rickey not only was the all-time leader in runs scored – the entire point of the sport – but also in unintentional walks, demonstrating his remarkable ability to get on base and make something happen when he did.

But you also can’t discount that in his 130-steal season, Rickey was caught an astounding 42 times – so his percentage in 172 attempts was 76%. That’s not terrible, but he still ran himself off the bases 42 times. Last year’s MLB steals leader, the immortal Willy Taveras, stole 68 bases – hardly 130 – but he was caught just 7 times (90%).

In that 1982 season, add up his hits, walks and HBP, take out his homers and triples (when he likely wouldn’t be stealing a base) and it comes to 247 – and he ran 172 times, 69% of the times he put himself on base. I’ll take out his two steals of home and the 19 times he stole multiple bases successively after getting on, and it still comes to 61%. (I admit, it’s an inexact science because it doesn’t factor in getting on base via fielder’s choices, errors and things of that nature, but it’s still telling)

What does this tell me? Six out of 10 times he got on base, Rickey was going to attempt to steal. Did that include times when it would probably benefit his team more if he didn’t attempt to steal? Most likely, but Rickey had Lou Brock’s record to break.

You might be asking, “What the hell is this guy basing this on?†Well, if the numbers don’t do anything for you, consider this at least partially a character study.

- I think most Yankees fans that saw Rickey halfheartedly run for fly balls over his head and go half-speed on the bases to protest his contract – until he was traded back to the A’s – would question whether winning was his true motivation.

- Amazingly, all A’s fans seem to love Rickey unconditionally – even though he dogged it like nobody’s business in 1992 after Jose Canseco received a contract greater than his.

- I watched Rickey intently both as a player for the Mets and later as a coach. And my friends, Rickey… was all about Rickey! You can start with the card game with Bonilla while the 1999 Mets were fighting for their lives in Game 6 of the NLCS. And after hearing ad nauseum how much Jose Reyes learned about plate discipline and basestealing from Rickey, we all had to watch as he demonstrated that he’d also learned from his mentor how to be a diva prone to a weird, moody attitude and extended funks at the plate and in the field, which in part likely contributed to the team’s disastrous collapse of ‘07.

- If Rickey was so amazingly valuable, why did he change teams 13 times? When it came down to it, despite his physical gifts, Rickey was not an easy guy to have around.

I’m not taking away the incredible disruption that Rickey could create – for his opponents, even more so than his own team – nor the fact that he could take over a game singlehandedl y if he deigned to. I’m also not taking away that nobody was better at reading a pitcher and a situation to steal a base; he made it an art form that was glorious to watch. And I admit to having watched live his steal of third to break Lou Brock’s career record, and being delighted to witness it.

y if he deigned to. I’m also not taking away that nobody was better at reading a pitcher and a situation to steal a base; he made it an art form that was glorious to watch. And I admit to having watched live his steal of third to break Lou Brock’s career record, and being delighted to witness it.

This is just a reminder to take the bad with the good. Rickey won a championship with the A’s in 1990 and another with the Blue Jays in 1993, and his vast talent was of course instrumental in both of them. Rickey was not merely along for the ride.

But while you celebrate his induction into the Hall this weekend – and his speech, which I admit was entertaining, though I’d imagine he had some help with it – just remember that when it came down to it, Rickey was all about Rickey. Why else would he keep attempting comebacks long after his prime? I realize he was in great condition until the end – probably still is – but he just wanted to tack on to his numbers to make sure nobody would match them.

Oh right, I forgot, he loved the game.

Do his negatives diminish his talent or accomplishments? Of course not. And the same traits that made Rickey exasperating at times are likely the same ones that helped make him great.

But if you tell Rickey’s story, just make sure you tell the whole thing.